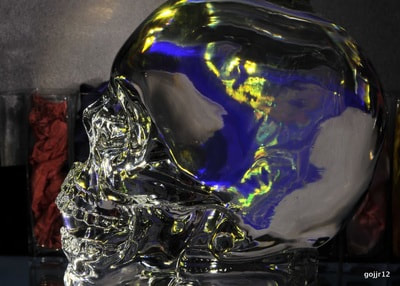

CALAVERAS RESPLANDECENTES 2006 - 2012

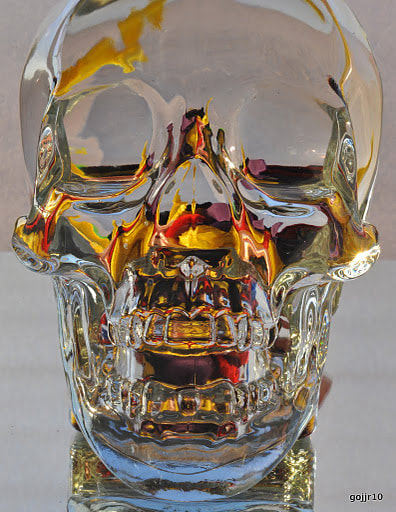

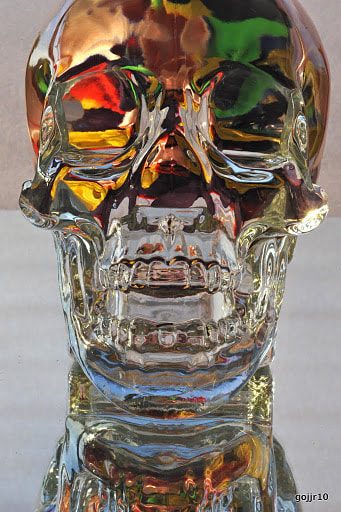

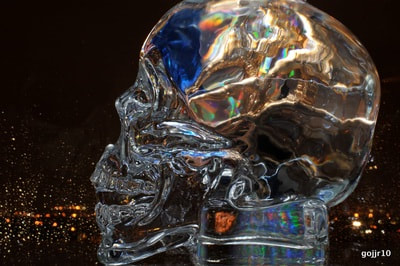

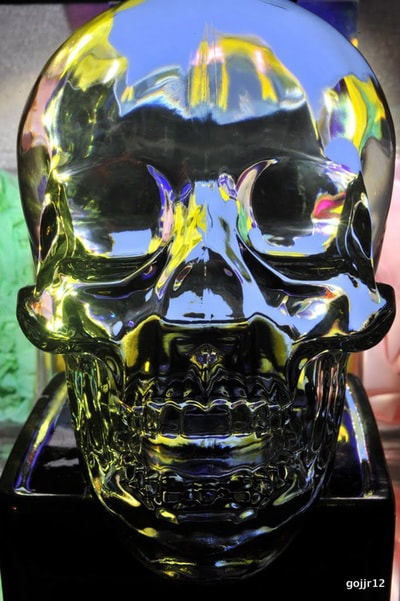

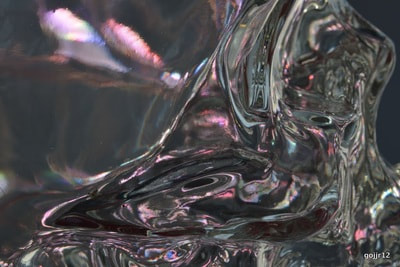

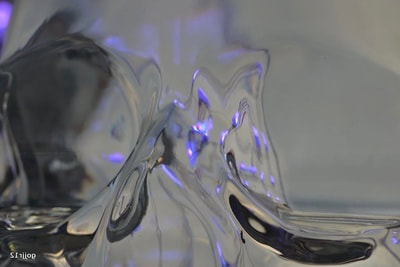

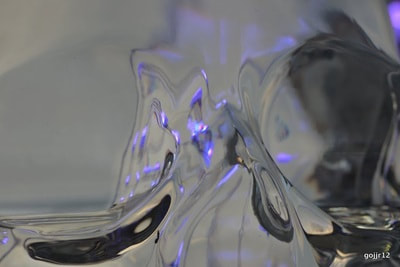

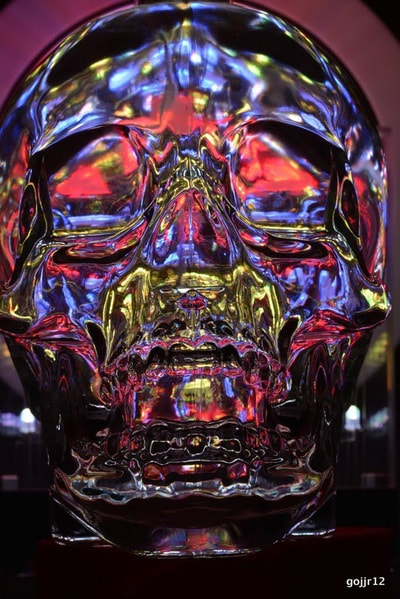

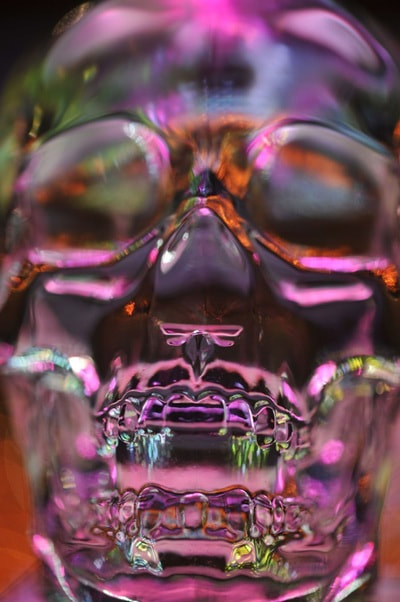

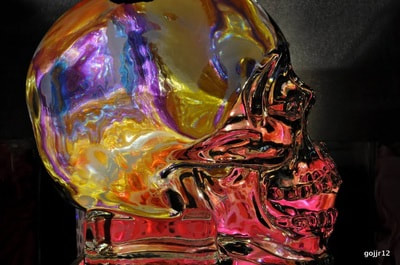

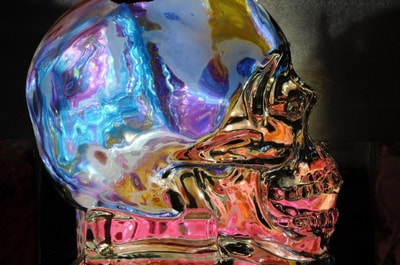

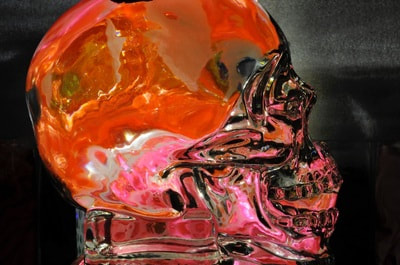

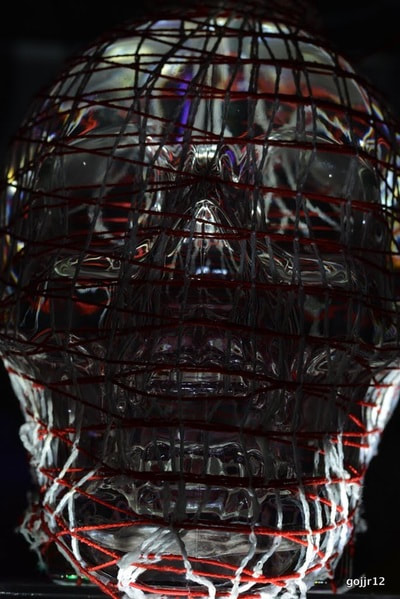

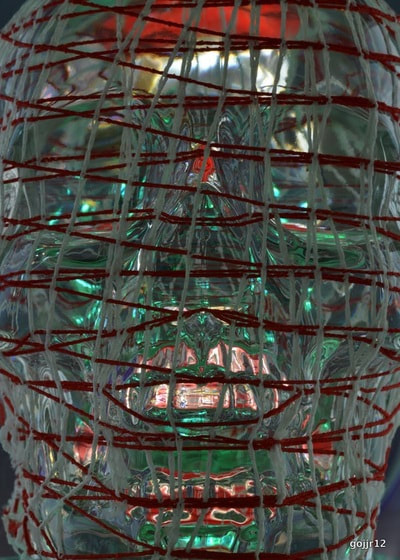

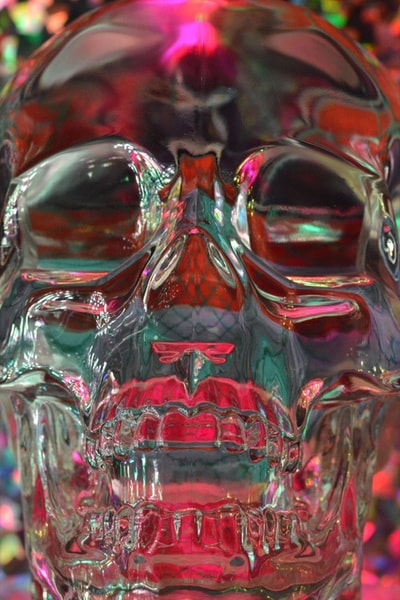

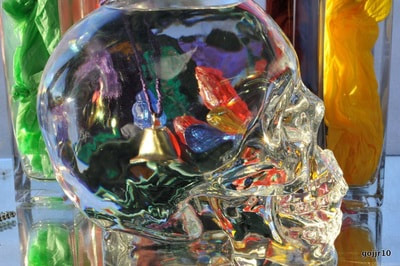

This series of photographs arose out of my fascination with color and light, which I found in refracted abundance in a skull-shaped vodka bottle that could be made to express a range of emotion, thought, and associations, as well as beautiful abstract patterns. The creative technique that I invented to do this uses ordinary materials that I discover in everyday places, drawn by their unusual colors and textures. I also use different light sources such as my iPhone flashlight. Experimenting with different palettes and light has been highly rewarding. The only limit to the creative potential of the glass skull was my own imagination.

I recognized the unusual power of the vodka bottle when it winked at me as it went up on the shelf. I noticed how it changed and adapted to the light and colors of its surroundings, and I succumbed to its dynamic spell.

Perhaps I became possessed by the glass skull. But I am not the first. People have been contemplating skulls throughout history-and throughout the history of art-reflecting on life, death, vanity, fear, the unknown, the occult, reason and the irrational, among other things, even the act of contemplation itself. The human skull-the death’s-head-is a potent symbol.

These Calaveras photographs are sometimes assembled in groups that I call a “tzompantli,” the Aztec name for the skull racks or walls of skulls that they and other pre-Columbian peoples built with the heads of the vanquished.

The power of the death’s head, along with the skeleton itself, remains dramatically alive in popular culture, especially in Mexico, in the masks and costumes of the seasonal religious festivals there and in the dancing skeletons and traditional sugar skulls that come back to lecture, warn, mock and make fun of us vain and foolish mortals every year on Day of the Dead.

I recognized the unusual power of the vodka bottle when it winked at me as it went up on the shelf. I noticed how it changed and adapted to the light and colors of its surroundings, and I succumbed to its dynamic spell.

Perhaps I became possessed by the glass skull. But I am not the first. People have been contemplating skulls throughout history-and throughout the history of art-reflecting on life, death, vanity, fear, the unknown, the occult, reason and the irrational, among other things, even the act of contemplation itself. The human skull-the death’s-head-is a potent symbol.

These Calaveras photographs are sometimes assembled in groups that I call a “tzompantli,” the Aztec name for the skull racks or walls of skulls that they and other pre-Columbian peoples built with the heads of the vanquished.

The power of the death’s head, along with the skeleton itself, remains dramatically alive in popular culture, especially in Mexico, in the masks and costumes of the seasonal religious festivals there and in the dancing skeletons and traditional sugar skulls that come back to lecture, warn, mock and make fun of us vain and foolish mortals every year on Day of the Dead.